The Privacy Angle Of UPI

On UPI platforms, where transactions take place via third-party gateways, who has the access to your data? and who will be responsible in case of a breach?

Hey!

Soooo this issue is going to be about UPI (yet again). I know this was supposed to be about the Account Aggregator framework and DEPA, but someone recently asked me what happens to the data shared on third-party apps offering UPI-related services, and honestly, it felt like a rabbit hole worth diving into before we move on.

Sorry about being THIS erratic, but let’s get started!

Last time when we discussed UPI, iwe mostly explored how it began and how far it has come. A substantial question we left out was how data processing works and what happens in case there is a breach of a user’s privacy. In normal transactions where a bank acts as an intermediary, it’s easy to trace where your sensitive financial data is going. In case of a breach, you can point out the source responsible for it (more or less). But when you use digital payment apps that act as intermediaries—just gateways between your bank and the merchant—who actually has access to your data? Where does it go? Who sees it?

Before we get into the privacy/breach bit, let’s quickly understand who’s involved in a UPI transaction in the first place. Here’s a simplified breakdown of how it looks:

Or at least how you think it looks.

Let’s zoom in on the network a little more.

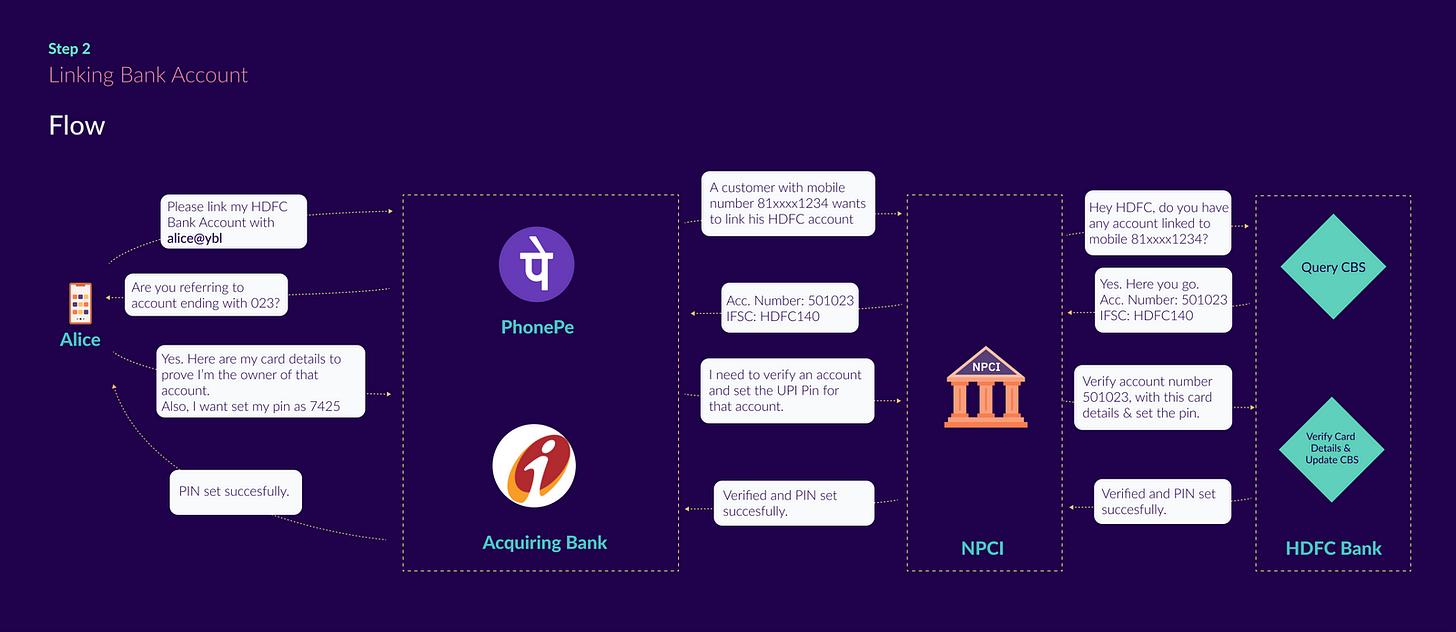

Once you register on a third-party app (like Google Pay, PhonePe, etc.), onboarding and linking your bank account goes something like this:

Key players in this onboarding process:

PhonePe – Third Party App Provider (TPAP): An app that facilitates open banking features like UPI.

ICICI Bank – Acquiring Bank: The bank that processes payments for the app.

NPCI – The RBI-created body that operates retail payment systems in India.

HDFC Bank – Issuing Bank: The bank that holds your account.

(I promise I’m not getting into the technicalities of how a transaction happens. I’m focusing on data sharing. But if you are curious, here’s a three-part explainer that breaks it all down. Knock yourselves out!)

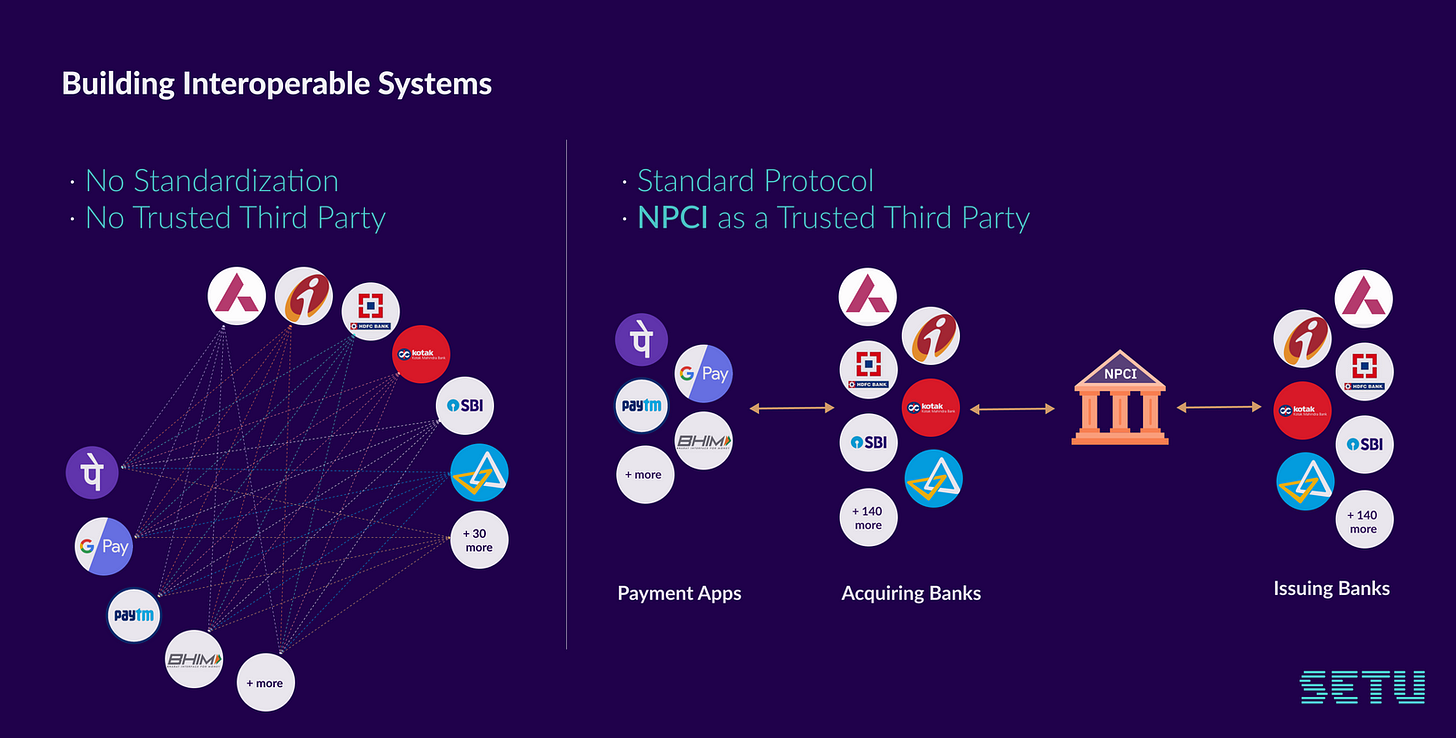

So now we know that a single transaction involves multiple parties. Let’s minimize that view and look at the UPI data-sharing ecosystem, it’s pretty vast.

The reason I’m showing you this is simple: the more parties involved, the harder it gets to trace who exactly has access to your data. Especially when non-banking apps come into play. Sure, there are financial regulations in place, but they don’t always cover data privacy. That’s a separate beast altogether.

And right now, that beast is barely tamed.

Without a solid data protection law (YET), companies like Facebook entering the payments space (hello, WhatsApp Pay) means your data could be up for grabs. Considering the whole Pegasus fiasco and WhatsApp’s history of sharing data with Meta, handing over access to your financial info feels… risky. And it’s not just them—plenty of non-compliant apps still operate with access to millions of users' data.

Now, back to the issue at hand.

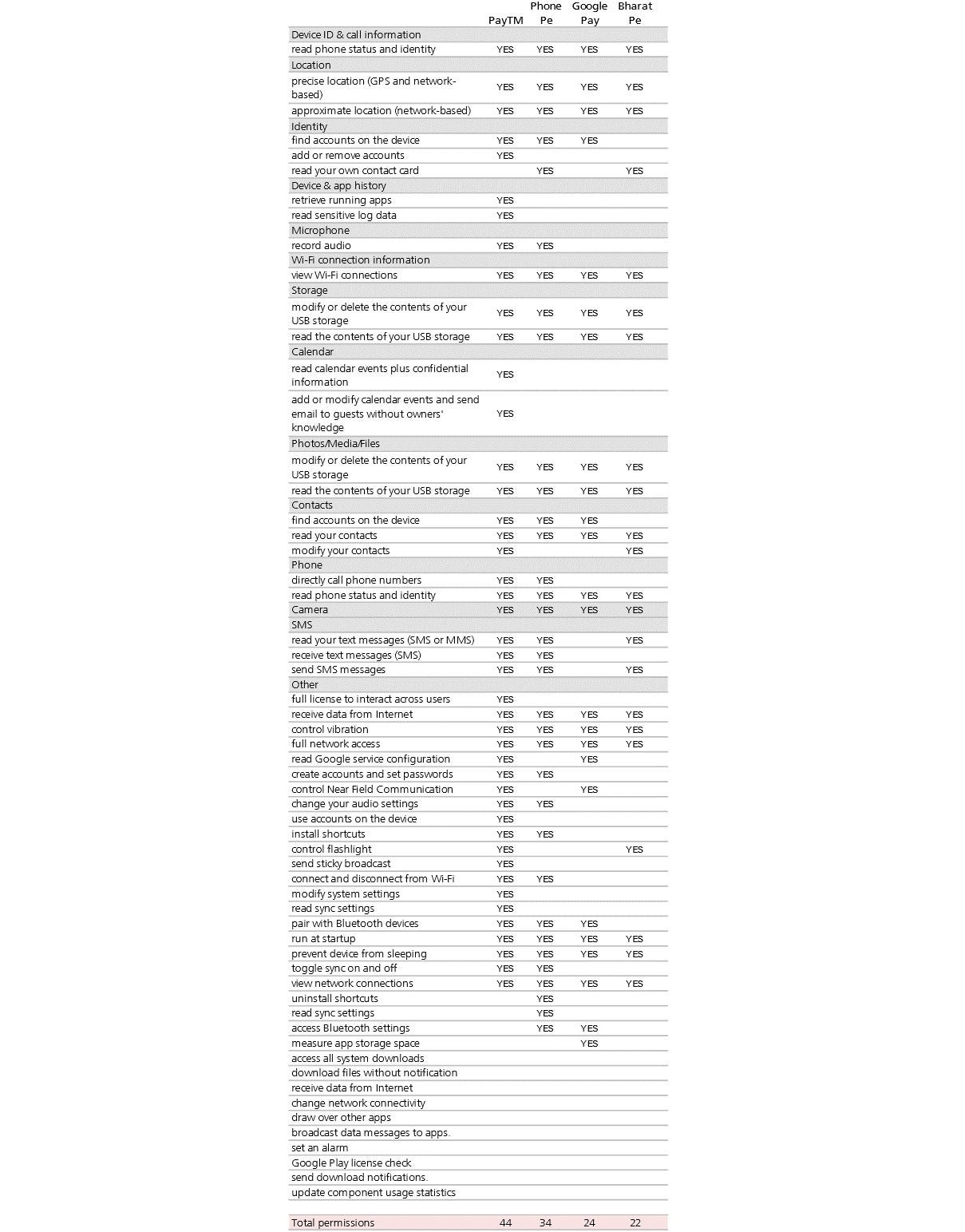

Besides the usual KYC documents needed to prove your identity, different platforms ask for very different permissions. Here’s a quick snapshot of what four major payment apps ask for:

On a lighter note though,

(From wanting access to your phone’s flashlight (understandable) to the voice recorder (???), PayTM really wants it ALL.)

These permissions are why you can send money to a phone contact or use your torch to scan a QR code in the dark. Some are necessary. Others? Debatable. RBI does allow the collection of user data but mandates an audit on its usage. Still, that doesn’t cover everything. (More on this later.)

Now, onto my favourite part—BREAAAACH!

With so many players involved, especially third-party apps with non-financial roots, data leaks are practically inevitable. The first red flags showed up back in 2017, when banks raised concerns about these apps accessing UPI data. This sparked a bit of a turf war: banks accused these apps of regulatory arbitrage. (More like regulatory arbit-RAGE, am I right?)

Naturally, the RBI (presumably) stepped in with more regulations—but breaches didn’t stop. One particularly scary case even had documented proof, but NPCI just decided to... shrug it off? Then came 2020, when a Public Interest Litigation (PIL) was filed in the Supreme Court over the misuse of consumer data by big payment platforms, arguing it violated citizens’ fundamental right to privacy.

[1. I agree that this was three years too late but at least we got there;

2. (I think) Since waiting around for a data protection bill was taking forever, someone just got tired of sitting around and decided to take one for the team and we should be grateful for it:’)]

The PIL was filed by Rajya Sabha MP Binoy Viswam (CPI), demanding safeguards for Indian citizens’ UPI data. The petition pointed out how tech giants like Amazon, Google, and Facebook/WhatsApp had been allowed into the UPI ecosystem despite violating UPI guidelines and RBI norms. This was taken up by the apex court in late 2020, which is why the proceedings are still ongoing and there hasn’t been any disruptive change yet. This case, Binoy Viswam vs RBI1, saw a counter-affidavit being filed by RBI which stated that not only is none of this RBI’s responsibility but also that matters relating to data sharing and processing come under the purview of the central government. Further, it even rejected the plea that it was under the obligation to audit firms engaged in UPI transactions and shifted the onus on its subsidiary NPCI, which is technically the owner and operator of UPI. Apart from this fantastic blame game, not much has happened. However, so far, the tech giants have been asked to file compliance reports, with a special emphasis on WhatsApp (Thank you, Pegasus).

So where does that leave us?

In a hot mess. There’s still no comprehensive protection for your data. Until we get a proper Personal Data Protection law, or until regulations grow teeth, we’re just sort of... winging it.

Thank you for reading!

Until Next time,

Drishti

WP 1038 of 2020

The cover photo is an edit of the illustration Norma Bar did for The Telegraph Magazine.

Highly informative.